Adam Larson/Caustic Logic

Guerillas Without Guns/Chapter 7

Posted 5/9/07

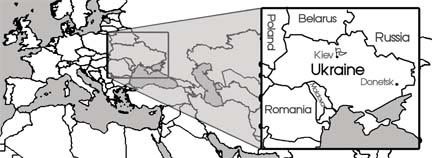

Russia’s response to the assault on its European periphery states in 2003-2004 demonstrates two unique and related historical patterns. The first is Russia’s split personality, straddling the arguably imaginary line that separates Europe from Asia. Russian thinkers have tackled the issue of Asian vs. European identity for centuries. Peter the great tried to settle this in 1703 by founding St. Petersburg and tying Russia into Europe’s affairs, but during the Great Game with England over Central Asia in the 1800s again European vs. Eastern/Asian/other became the paradigm. Since the Bolsheviks moved the capitol back to Moscow, and more so since the collapse of the USSR, Russia's European aspirations have been lessened in favor of a centralizing view that looks south and east as well as west.

The other key factor is Russia’s tactic of withdrawal when threatened, as they did when Napoleon invaded. Moscow was abandoned and burnt to the ground, leaving nothing for the French army, most of whom died in the attempt to get back home ahead of winter. When things get rough on the European front, Russians pull back to the east, relying on the continental vastness of their Eurasian territory to wait out the crisis.

2004-05 was such a time, and indeed Russia’s power focus has to a remarkable degree shifted east as ambitions in Europe slid into political obscurity. It’s not so much that the Kremlin has abandoned its plans for Europe as that it is diversifying its holdings and making contingency plans for an uncertain future there. So Putin’s Moscow started taking greater interest in increasing control over its former Central Asian holdings; the independent but cooperative nations of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and to a much lesser extent ‘neutral” Turkmenistan.

The Central Asian Republics seemed relatively safe from the Orange Revolution type of tactic. In Europe there is the EU, NATO, and a long history of Democratic institutions and mindsets. But these landlocked Muslim-dominated nations, resource-rich but impoverished and still run largely on Soviet habits and older memories, lie in an area still jointly dominated by “great power rivals” Russia and China. Central Asia is a long way from Brussels – and so as the democratic bridgehead struggled to cross the last spans of Europe, this was the Bulkhead of Russia’s Eurasian power outside its own borders.

The area also represents the heart of “the Grand Chessboard” of Eurasia as portrayed by Zbigniew Brzezinski. He describes this region as the “Eurasian Balkans,” encompassing the Caucasian and Central Asian flanks of the former USSR plus Iran and Afghanistan. Compared to the European Balkans, “the Eurasian Balkans are infinitely more important as a potential economic prize,” at twenty times the size and presenting an enormous zone of instability “astride the inevitably emerging transportation network meant to link [Eurasia’s] western and eastern extremities.” [1] Thus as in times ancient, the region was to be the crossroads of Eurasia, host to a 21st Century Silk Road as Unocal called it – pipelines, fiber optic cable, superhighways, all facilitating further globalization of a previously under-tapped region.

There was more than transport at stake though; Central Asia straddles the Himalayan foothills, producing a tectonic cornucopia of mineral wealth, including tin, gold, and platinum in large quantities. And to a world increasingly thirsty for oil and natural gas, Central Asia has stood out for one key reason – the energy reserves of the Caspian Sea; Fortunes and political careers were made and broken in what Ahmed Rashid in 1997 dubbed “the New Great Game.” After 9/11 we found that the prize was not as big as originally thought, (and hence the war was not about that). But by mid-2006, world oil prices climbed from a pre-9/11 baseline of about $25 a barrel to well over $70 a barrel, US News and World Report noted in their September 11 2006 issue “the stakes have suddenly shot up,” and interest is now as intense as ever. [2]

---

Next: From Shanghai with Love: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization

Sources:

[1] Brzezinski. "The Grand Chessboard." 1997. Page 124.

[2] Fang, Bay. “The Great Energy Game.” US News and World Report. Vol 141, no. 9. September 11 2006. p 60-62.

Showing posts with label Brzezinski Z. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Brzezinski Z. Show all posts

Saturday, May 26, 2007

Thursday, May 10, 2007

EURO-NATO: HOW THE WEST WAS RUN

Adam Larson/Caustic Logic

Guerillas Without Guns/Chater 1

Poated 5/11/2007

One of the prime avenues for containing and steering the power of the EU into conformity with the Anglo-American Alliance was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Also called “the Western Alliance:” the US, UK, Belgium, France, et al, NATO was the grand World War II Alliance minus the USSR. After forming in 1949, NATO took in Greece and Turkey (1952), and then West Germany (1955), but afterwards sat steady for decades as it stared Moscow down, never used its mutual defense clause, and remained a potential military force only.

Yet despite the final crumbling of the Warsaw Pact and even the USSR itself, the objects of its vigilance, NATO remained and looked for a new mission. In a 1992 Pentagon report leaked before scrubbing, then Undersecretary of Defense for policy Paul Wolfowitz offered a role for NATO if not a mission. The report admitted “we must seek to prevent the emergence of European-only security arrangements which would undermine NATO, particularly the alliance’s integrated command structure.” This command structure keeps the United States in the loop so that the Europeans could not make military or security decision the US was unwilling to sign off on. Indeed, Wolfowitz noted how this arrangement would allow NATO to remain “the primary instrument of Western defense and security as well as the channel for U.S. influence and participation in European security affairs.” [1]

CFR heavyweight and former National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski saw the same role for NATO. In his 1997 strategic tome The Grand Chessboard, he took a placating line that the organization’s leadership should eventually give Europe a greater role, coequal with Washington in a 1+1 (US + EU) formulation. While he noted the existing “American primacy within the alliance,” European membership was set to grow, and thus “NATO will have to adjust.” [2] But in an accompanying article for Foreign Affairs, the official publication of the CFR, he wrote more frankly:

“With the allied European nations still highly dependent on US protection, any expansion of Europe's political scope is automatically an expansion of US influence. […] A wider Europe and an enlarged NATO will serve the short-term and longer-term interests of US policy. A larger Europe will expand the range of American influence without simultaneously creating a Europe so politically integrated that it could challenge the United States...” [3]

To date, NATO remains Europe’s only credible security force, is now in fact waging wars over its member’s interests while expanding its member list (and therefore possible conflict trigger-points), and the US has consistently promoted European expansion, especially the CFR people.

Who exactly is pulling whose strings in this arrangement is a matter of contention. Some, like John Laughland, would argue that Europe has thus been made the “51st state of America,” [4] while some Americans claim their country has been “Europeanized” as the economic powerhouse to bolster the European order. More likely neither side holds the reins exclusively, and a carefully managed confluence of interests is the wellspring of this trans-Atlantic union we call the West. Either way, regarding Russia and its sphere, it can be treated as a unified and hungry whole. Upon the USSR's collapse, if not before, the West set to wooing the former Warsaw Pact states; Internal political and economic reforms, once verified, could lead to inclusion in the solidifying EU and even NATO, then taking new applications as it considered its new agenda.

It was known Russia could not react favorably to NATO expansion, as noted in a 1995 analysis by Alexei K. Pushkov, onetime adviser and speech-writer for Premier Gorbachev, an eminent Russian mind. The report was published in Strategic Forums, an offshoot of National Defense University in Washington, and warned that NATO expansion into Eastern Europe or beyond would lead to seven key problems. Pushkov listed among these: “deepening of the gap between Russian and Western civilizations,” “an unwelcome influence on internal Russian politics,” and “a rebirth of the Russian sphere of influence among the former states of the Soviet Union.” On this point, he explained “if Russia considers itself geopolitically cut off from Europe and the Euro-Atlantic community, it would have no choice but to strengthen its historical sphere of influence.” [5]

Most ironically, Pushkov predicted, the expansion of this tool of Western security could well lead to “a weakening of overall European security” by expanding the number of NATO’s mutual defense trigger points while simultaneously increasing the tensions with Russia over those, and by encouraging “a new militarism in Russia.” Expansion would surely be seen in Moscow as an unfriendly act of distrust, no matter the spin put on it, and could cause Russia “to become a more independent player, less constrained by a real or illusionary partnership with the West.” Pushkov warned “Russia might well become a loose cannon in world politics” with “very serious” effects on world stability.

Yet in March 1999 the NATO blithely accepted applications from former Warsaw Pact states Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, expanding its geographic scope greatly at the expense of Russia’s recent sway. Others got in the queue; Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, the last Republics fused into the USSR and first to leave, ran away and joined this circus. A later round of NATO additions in March 2004 scored all three, its first former SSRs, along with Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and the alliance’s first former Yugoslav republic, Slovenia.

left: NATO states vs. Warsaw Pact in 1988, Iron Curtain highlighted.

right: NATO vs. Russia’s sphere (CIS) in mid-2004

During the Cold War the West always maintained they propped up the Iron curtain to keep the Soviet wolf at bay – in its time that may have been true, but once the fence fell, every bit of devouring has been in an easterly direction as the Euro-Atlantic community expands deeper into Eurasia and what was being called the post-Soviet Space, with Russia’s influence receding like a melting glacier.

Next: Gene Sharp: Master of Noviloent Warfare

Sources:

[1] Tyler, Patrick E. "US Strategy Plan Calls for Insuring No Rivals Develop A One-Superpower World: Pentagon’s Document Outlines Ways to Thwart Challenges to Primacy of America." The New York Times. March 8, 1992.

http://work.colum.edu/~amiller/wolfowitz1992.htm

[2] Brzezinski, Zbigniew. "The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives." New York. Basic Books. 1997. First Printing. Page 76

[3] Zbigniew Brzezinski, "A Geostrategy for Eurasia," Foreign Affairs, 76:5, September/October 1997.

http://www.comw.org/pda/fulltext/9709brzezinski.html

[4] Laughland, John. “Becoming the 51st State.” Antiwar.com. May 20, 2003

http://antiwar.com/laughland/?articleid=2071

[5] Pushkov, Alexei. "NATO Enlargement: A Russian Perspective." Strategic Forums. July 1995. http://www.ndu.edu/inss/strforum/SF_34/forum34.html

Guerillas Without Guns/Chater 1

Poated 5/11/2007

One of the prime avenues for containing and steering the power of the EU into conformity with the Anglo-American Alliance was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Also called “the Western Alliance:” the US, UK, Belgium, France, et al, NATO was the grand World War II Alliance minus the USSR. After forming in 1949, NATO took in Greece and Turkey (1952), and then West Germany (1955), but afterwards sat steady for decades as it stared Moscow down, never used its mutual defense clause, and remained a potential military force only.

Yet despite the final crumbling of the Warsaw Pact and even the USSR itself, the objects of its vigilance, NATO remained and looked for a new mission. In a 1992 Pentagon report leaked before scrubbing, then Undersecretary of Defense for policy Paul Wolfowitz offered a role for NATO if not a mission. The report admitted “we must seek to prevent the emergence of European-only security arrangements which would undermine NATO, particularly the alliance’s integrated command structure.” This command structure keeps the United States in the loop so that the Europeans could not make military or security decision the US was unwilling to sign off on. Indeed, Wolfowitz noted how this arrangement would allow NATO to remain “the primary instrument of Western defense and security as well as the channel for U.S. influence and participation in European security affairs.” [1]

CFR heavyweight and former National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski saw the same role for NATO. In his 1997 strategic tome The Grand Chessboard, he took a placating line that the organization’s leadership should eventually give Europe a greater role, coequal with Washington in a 1+1 (US + EU) formulation. While he noted the existing “American primacy within the alliance,” European membership was set to grow, and thus “NATO will have to adjust.” [2] But in an accompanying article for Foreign Affairs, the official publication of the CFR, he wrote more frankly:

“With the allied European nations still highly dependent on US protection, any expansion of Europe's political scope is automatically an expansion of US influence. […] A wider Europe and an enlarged NATO will serve the short-term and longer-term interests of US policy. A larger Europe will expand the range of American influence without simultaneously creating a Europe so politically integrated that it could challenge the United States...” [3]

To date, NATO remains Europe’s only credible security force, is now in fact waging wars over its member’s interests while expanding its member list (and therefore possible conflict trigger-points), and the US has consistently promoted European expansion, especially the CFR people.

Who exactly is pulling whose strings in this arrangement is a matter of contention. Some, like John Laughland, would argue that Europe has thus been made the “51st state of America,” [4] while some Americans claim their country has been “Europeanized” as the economic powerhouse to bolster the European order. More likely neither side holds the reins exclusively, and a carefully managed confluence of interests is the wellspring of this trans-Atlantic union we call the West. Either way, regarding Russia and its sphere, it can be treated as a unified and hungry whole. Upon the USSR's collapse, if not before, the West set to wooing the former Warsaw Pact states; Internal political and economic reforms, once verified, could lead to inclusion in the solidifying EU and even NATO, then taking new applications as it considered its new agenda.

It was known Russia could not react favorably to NATO expansion, as noted in a 1995 analysis by Alexei K. Pushkov, onetime adviser and speech-writer for Premier Gorbachev, an eminent Russian mind. The report was published in Strategic Forums, an offshoot of National Defense University in Washington, and warned that NATO expansion into Eastern Europe or beyond would lead to seven key problems. Pushkov listed among these: “deepening of the gap between Russian and Western civilizations,” “an unwelcome influence on internal Russian politics,” and “a rebirth of the Russian sphere of influence among the former states of the Soviet Union.” On this point, he explained “if Russia considers itself geopolitically cut off from Europe and the Euro-Atlantic community, it would have no choice but to strengthen its historical sphere of influence.” [5]

Most ironically, Pushkov predicted, the expansion of this tool of Western security could well lead to “a weakening of overall European security” by expanding the number of NATO’s mutual defense trigger points while simultaneously increasing the tensions with Russia over those, and by encouraging “a new militarism in Russia.” Expansion would surely be seen in Moscow as an unfriendly act of distrust, no matter the spin put on it, and could cause Russia “to become a more independent player, less constrained by a real or illusionary partnership with the West.” Pushkov warned “Russia might well become a loose cannon in world politics” with “very serious” effects on world stability.

Yet in March 1999 the NATO blithely accepted applications from former Warsaw Pact states Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, expanding its geographic scope greatly at the expense of Russia’s recent sway. Others got in the queue; Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, the last Republics fused into the USSR and first to leave, ran away and joined this circus. A later round of NATO additions in March 2004 scored all three, its first former SSRs, along with Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and the alliance’s first former Yugoslav republic, Slovenia.

left: NATO states vs. Warsaw Pact in 1988, Iron Curtain highlighted.

right: NATO vs. Russia’s sphere (CIS) in mid-2004

During the Cold War the West always maintained they propped up the Iron curtain to keep the Soviet wolf at bay – in its time that may have been true, but once the fence fell, every bit of devouring has been in an easterly direction as the Euro-Atlantic community expands deeper into Eurasia and what was being called the post-Soviet Space, with Russia’s influence receding like a melting glacier.

Next: Gene Sharp: Master of Noviloent Warfare

Sources:

[1] Tyler, Patrick E. "US Strategy Plan Calls for Insuring No Rivals Develop A One-Superpower World: Pentagon’s Document Outlines Ways to Thwart Challenges to Primacy of America." The New York Times. March 8, 1992.

http://work.colum.edu/~amiller/wolfowitz1992.htm

[2] Brzezinski, Zbigniew. "The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives." New York. Basic Books. 1997. First Printing. Page 76

[3] Zbigniew Brzezinski, "A Geostrategy for Eurasia," Foreign Affairs, 76:5, September/October 1997.

http://www.comw.org/pda/fulltext/9709brzezinski.html

[4] Laughland, John. “Becoming the 51st State.” Antiwar.com. May 20, 2003

http://antiwar.com/laughland/?articleid=2071

[5] Pushkov, Alexei. "NATO Enlargement: A Russian Perspective." Strategic Forums. July 1995. http://www.ndu.edu/inss/strforum/SF_34/forum34.html

Thursday, February 22, 2007

FROM SHANGHAI WITH LOVE

THE SCO BEFORE AND AFTER 9/11

Adam Larson

Caustic Logic / Guerillas Without Guns

Western access to the "Eurasian Balkans" of Central Asia relied on the post-Cold War dissolution of Soviet power that opened the area to outside influence – and such a situation was not necessarily permanent. Brzezinski noted in 1997 early fears of a new convergence of native Eurasian power: “if the middle space [Russia and former USSR] rebuffs the West, becomes an assertive single entity, and either gains control over the South [Central Asia] or forms an alliance with the major Eastern actor [China], then America's primacy in Eurasia shrinks dramatically.” Indeed, the seeds for all these possibilities were already sown as he wrote the words.

Perhaps the most interesting of these started as the quaint-sounding “Shanghai Five” organizations that was formed in 1996 with signatory nations China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. With official languages of Russian and Chinese, they worked to resolve border and disarmament disputes between themselves, apparently a regional house-cleaning in preparation for a more muscular campaign.

In their sixth annual meeting, June 2001 in Shanghai, sixth member Uzbekistan was admitted and the group re-named itself the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), with stated aims of fighting ethnic and religious militancy and promoting trade and foreign investment. Gradually in the years since then, the SCO also came to be seen as an alternative to US power in Central Asia; by the middle of 2005 its platform was broad enough to entice Mongolia, Iran, Pakistan, and India to sign on as observer states and consider joining (see map). Obviously the possibility of membership for any of these states is loaded with deep implications for the existing world system, a hope for many and a fear for others that has underpinned events in Eurasia in the years since.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization: member states and observer states. Note the total domination of Eurasia this could lead to.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization: member states and observer states. Note the total domination of Eurasia this could lead to.

From the beginning, the member governments of the SCO had been focused on collective security, counter-terrorism work, and anti-narcotics operations. They thus shared a concern over the lawless state in the Taliban’s Afghanistan, rife with civil war and oozing out a steady stream of Islamic fundamentalism, trained terrorists, and opium. The training camps attributed widely to bin Laden’s al Qaeda were primarily meant to usher in Islamist governments in regional states and areas like Xinjiang, Chechnya, and Uzbekistan, so this was clearly a paramount regional concern. The Taliban’s prime sponsor, Pakistan, was nowhere near the SCO at the time, but India, Iran, and Russia had all teamed up to support the Northern Alliance against the Taliban however they could. The Alliance was offered safe haven in Tajikistan to bolster its position on Afghanistan’s northern fringe. After 9/11 and the commencement of Washington’s “War on Terror,” the SCO issued a sort of ‘told-you-so’ statement on January 7 2002:

“As close neighbors of Afghanistan we had for an extended time been directly subjected to the terrorist and narco threats emanating from its territory long before the events of September 11 and had repeatedly warned the international community of the danger posed by those threats. That was why the SCO member states became actively involved in the anti-terrorist coalition and took measures to further intensify the SCO's work on the anti-terrorist front.” [3]

Sources:

[1] Brzezinski. "The Grand Chessboard." 1997. Page 124.

[2] Fang, Bay. “The Great Energy Game.” US News and World Report. Vol 141, no. 9. September 11 2006. p 60-62.

[3] Joint Statement by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (Beijing, January 7, 2002) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. http://www.shaps.hawaii.edu/fp/russia/sco_3_20020107.html

Adam Larson

Caustic Logic / Guerillas Without Guns

Western access to the "Eurasian Balkans" of Central Asia relied on the post-Cold War dissolution of Soviet power that opened the area to outside influence – and such a situation was not necessarily permanent. Brzezinski noted in 1997 early fears of a new convergence of native Eurasian power: “if the middle space [Russia and former USSR] rebuffs the West, becomes an assertive single entity, and either gains control over the South [Central Asia] or forms an alliance with the major Eastern actor [China], then America's primacy in Eurasia shrinks dramatically.” Indeed, the seeds for all these possibilities were already sown as he wrote the words.

Perhaps the most interesting of these started as the quaint-sounding “Shanghai Five” organizations that was formed in 1996 with signatory nations China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. With official languages of Russian and Chinese, they worked to resolve border and disarmament disputes between themselves, apparently a regional house-cleaning in preparation for a more muscular campaign.

In their sixth annual meeting, June 2001 in Shanghai, sixth member Uzbekistan was admitted and the group re-named itself the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), with stated aims of fighting ethnic and religious militancy and promoting trade and foreign investment. Gradually in the years since then, the SCO also came to be seen as an alternative to US power in Central Asia; by the middle of 2005 its platform was broad enough to entice Mongolia, Iran, Pakistan, and India to sign on as observer states and consider joining (see map). Obviously the possibility of membership for any of these states is loaded with deep implications for the existing world system, a hope for many and a fear for others that has underpinned events in Eurasia in the years since.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization: member states and observer states. Note the total domination of Eurasia this could lead to.

Shanghai Cooperation Organization: member states and observer states. Note the total domination of Eurasia this could lead to. From the beginning, the member governments of the SCO had been focused on collective security, counter-terrorism work, and anti-narcotics operations. They thus shared a concern over the lawless state in the Taliban’s Afghanistan, rife with civil war and oozing out a steady stream of Islamic fundamentalism, trained terrorists, and opium. The training camps attributed widely to bin Laden’s al Qaeda were primarily meant to usher in Islamist governments in regional states and areas like Xinjiang, Chechnya, and Uzbekistan, so this was clearly a paramount regional concern. The Taliban’s prime sponsor, Pakistan, was nowhere near the SCO at the time, but India, Iran, and Russia had all teamed up to support the Northern Alliance against the Taliban however they could. The Alliance was offered safe haven in Tajikistan to bolster its position on Afghanistan’s northern fringe. After 9/11 and the commencement of Washington’s “War on Terror,” the SCO issued a sort of ‘told-you-so’ statement on January 7 2002:

“As close neighbors of Afghanistan we had for an extended time been directly subjected to the terrorist and narco threats emanating from its territory long before the events of September 11 and had repeatedly warned the international community of the danger posed by those threats. That was why the SCO member states became actively involved in the anti-terrorist coalition and took measures to further intensify the SCO's work on the anti-terrorist front.” [3]

Sources:

[1] Brzezinski. "The Grand Chessboard." 1997. Page 124.

[2] Fang, Bay. “The Great Energy Game.” US News and World Report. Vol 141, no. 9. September 11 2006. p 60-62.

[3] Joint Statement by the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Member States of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (Beijing, January 7, 2002) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. http://www.shaps.hawaii.edu/fp/russia/sco_3_20020107.html

Labels:

Afghanistan,

al Qaeda,

Brzezinski Z,

Central Asia,

China,

opium,

Russia,

SCO,

Taliban,

terrorism

Monday, February 19, 2007

BLEEDING RUSSIA: A DARK DECADE

OLIGARCHS, COLLAPSE, BAILOUT... THEN REVIVAL

Adam Larson

Caustic Logic / Guerillas Without Guns

Re-posted 2/17/07

For Washington and London, the ability to start making these pipeline power plays was both an effect and hopefully a further cause of Russia’s diminished regional power. Behind this seems to be a campaign to drag the Eurasian giant into the Euro-Atlantic Community kicking and foaming at the mouth if need be, an aim laid out well by Brzezinski in 1997: “Russia’s only real geostrategic option – the option that could give Russia a realistic international role and also maximize the opportunity of transforming and socially modernizing itself - is […] the transatlantic Europe of the enlarging EU and NATO.” Russia should follow this lead, Brzezinski warned, if it wanted to avoid “a dangerous geopolitical isolation.” [1]

But the exact terms of integration remained unclear; Russians somehow took Washington’s talk around 1992-93 of a “mature strategic partnership” as a revival of Gorbachev’s “new world order” scenario, a more-or-less co-equal global alliance of mutually existing great powers. Fawning praise, false promises, and the opening of economies ensued in a long and nearly snuggly phase that allowed what Brzezinski summed up as the Russian street’s expectation of “a global condominium.” Zbig noted in retrospect:

“The problem with this approach was that it was devoid of either international or domestic realism. While the concept of a “mature strategic partnership” was flattering, it was also deceptive. America was neither inclined to share global power with Russia nor could it, even if it had wanted to. […] once differences inevitably started to surface, the disproportion in political power, financial clout, technological innovation and cultural appeal made the “mature strategic partnership” seem hollow – and it struck an increasing number of Russians as deliberately designed to deceive Russia.” [2]

So it was not America’s fault, but the fact that Russia was simply not up to the role. But the 1990s did see economic liberalization in Yeltsin’s Russia, with the widespread privatization of the previously state-run enterprises and moves towards a full market economy, openness to foreign investment, and general integration with the Western system. The major enterprises were taken over by a new generation of Russian capitalist pioneers and black-marketeers known as “the Oligarchs.” First introduced to the scene by Gorbachev in the late 1980s under his perestroika campaign, President Yeltsin supported this process and provided the Oligarchs with rich pickings, and the very small group soon acquired vast interests in all sectors of the economy. But in the end analysis, everyone agrees that the oligarchs did not rescue the Russian economy but rather bled it dry. Journalist Ann Williamson, author of How America Built the New Russian Oligarchy, explained to the House Committee on Banking in her September 1999 testimony:

“Directors stashed profits abroad, withheld employees’ wages, and after cash famine set in, used those wages, confiscated profits and state subsidies to ‘buy’ the workers’ shares from them. The really good stuff – oil companies, metal plants, telecoms – was distributed to essentially seven individuals, ‘the oligarchs,’ on insider auctions whose results were guaranteed beforehand. Once effective control was established, directors - uncertain themselves of the durability of their claim to newly acquired property - chose to asset strip with impunity instead of developing their new holdings.” [3]

Profits thus gained were laundered and deposited safely in Western bank accounts outside of Russia’s reach, with the depositors sometimes following their money out the door. Passed off as the result of mismanagement and shortsighted greed, the draining of Russia’s treasury is usually termed as “capital flight,” a rather passive sounding process. But investigator Michael Ruppert sees geopolitics at work in this “scheme to loot Russia’s wealth and park it in the west.” Once they were granted positions of economic power, Ruppert maintained in his 2004 book Crossing the Rubicon that “the Empire loved the oligarchs because they were simple and could be easily controlled with money.” [4]

Ruppert also noted how the “assistance” program to usher Russia into capitalism took off under the Clinton administration in 1993. A team headed by vice president Al Gore worked in concert with Goldman Sachs, Harvard’s Institute for International Development, the IMF, and the World Bank. This team, as Ruppert summarized, “worked in partnership with the government of Boris Yeltsin to re-make the Russian economy. What happened was that Russia, in the words of Yeltsin himself, became a “mafiocracy” and was looted of more than 500 billion in assets, and its ability to support a world-class military establishment smashed.” [5] What a convenient turn of events against this recently identified potential rival.

Yeltsin had initially renounced all claim to former Soviet glory and empire: “Russia does not aspire to become the center of some sort of new empire […] history has taught us that a people that rules over others cannot be fortunate.” [6] But by 1997 as Brzezinski wrote his book, new ideas about Russia’s role were starting to gel in Moscow that showed signs of renewed ambition. Straddling the boundary between Europe and Asia, the idea of a special “Eurasianism” took hold; as Yeltsin’s former Vice President Aleksandr Rustkoi explained “Russia represents the only bridge between Asia and Europe. Whoever becomes the master of this space will become the master of the world.” [7] Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev said at around this time Russia “must preserve its military presence in regions that have been in its sphere of interests for centuries.” [8]

But not much was possible with the economy still in a weak transitional state. The first slight economic recovery began in 1997, but this was cut short by the Asian financial crisis that hit its markets late in the year. The nation toughed out the financial burden through the first half of 1998, but things got edgy as the money dried up. In May a campaign of pensioner’s strikes was joined by miner’s strikes and others – the people took matters into their own hands, blocking railway lines to demand unpaid back wages. Communist leader Gennady Zyuganov led the growing calls for Yeltsin and his newly-appointed PM Sergei Kiryenko to resign. [9]

Perhaps in desperation, Russia finally turned to the West and sought an IMF bailout, what Ruppert calls “the kiss of death for any country.” [10] The IMF reported it was strapped, and “entering a region in terms of our financing where we are in grave difficulties.” [11] Washington feared the alternative – a Russian devaluation of the ruble (their equivalent of the dollar), leading to an international financial chain reaction. [12] On July 20, the IMF Executive Board approved its portion ($11.2 billion) of a $22.6 billion international bailout. This emergency package was intended to help Russia maintain the value of the ruble while the government implemented reforms necessary to create long-term stability.

On August 14, president Yeltsin assured the west that the loan had worked, stating clearly that the ruble would not be devalued. But a bare three days later, PM Kiriyenko announced that the government would devalue the ruble after all, by a stunning 34 percent, and declared a 90-day foreign debt moratorium. The bottom dropped from beneath the Russian economy that very day, leading to a total collapse comparable to the crash that hit America’s markets in 1929.

Mass unemployment and a sharp fall in living standards for most of the population ensued. Unemployment, hunger, homelessness, and related social problems wracked the region in late 1998. CNN billed “Russia’s year of agony” as one of the top ten stories of the year, and it also spread into neighboring countries like Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, that remained tangled with their neighbor’s economy. Many in Washington were furious; Ariel Cohen and Brett Schaefer of the Heritage Foundation noted “it is now painfully clear […] that the massive bailout failed in both of its missions: The ruble was devalued, and reforms are not likely to be implemented.” Cohen and Schaefer blamed Russia for failing to reform its economy and the IMF for consistently loaning to them anyway, calling on Congress to cut off funding to the fund. [13]

The crisis did not last too long though on the Russian end; by whatever connection, it was only after the loan and the devaluation of the ruble and the debt default that Russia’s economy began improving on the back of strong gas exports in 1999. The weak ruble made imports expensive and boosted local production, creating greater self-reliance or “autarky,” the opposite of the economic “dependency model” behind the western system. Russia entered a phase of rapid economic expansion, the GDP growing by an average of 6.7% annually in 1999-2005 on the back of higher oil prices, a weaker ruble, and increasing industrial output. It has gone from bankruptcy to large foreign reserves, and by 2001 Russia was seen as a major rising player on the world scene for the first time in nearly a decade. In retrospect the IMF episode almost looks like a grand kiss-off to the West: “Thanks for the so-called assistance, comrades, but we’ll just recover what we can and manage it ourselves from there...”

Behind the official reasons for the 1998 bailout there had been deeper fears than the value of the ruble. The youngest and richest among the economy draining Russian Oligarchs is Roman Abramovich, in 2006 Russia’s richest man and the 11th richest person in the world, worth $18.2 billion. [14] Abramovich is a proud Jew and supporter of Israel, and he’s not alone; the top tier of Oligarchs were primarily Jews, a fact that contributed negatively to a trend all too familiar from the history books: a nation in crisis after losing a major struggle, feeling betrayed by the West and turning to renewed nationalist glory and – at least in certain cases - increased suspicion of the Jews among them. The specific anti-Semitism has of course become highly unpopular since the Holocaust, and precise charges have remained muted – but overall a repeat of Germany circa 1932 seemed a danger; the British free trade magazine The Economist ran a story on July 15 warning that an abrupt devaluation:

“could spell doom for the banking system, bring down the Kiriyenko government and, as one American diplomat put it, ‘signal the end of liberal Russia.’ […] Might the deadly mixture of economic chaos, public anger and sense of national humiliation that fuelled fascism in Weimar Germany flare up in Russia now? […] Such fears appear to have been taken seriously enough in Washington for the US administration to deem the situation in Russia to be a global strategic threat."[15]

Five days after this story ran the package was approved, but on this front as well the bailout seems to have had little effect. Prime Minister Kiriyenko was sacked in August. Yeltsin tried to bring back his predecessor Viktor Chernomyrdin, but in September compromised on Yevgeniy Primakov. In May 1999 Yeltsin sacked Primakov, replacing him with Sergey Stepashin, who served until August when Yeltsin replaced him with rising star Vladimir Putin. Putin was thus the fifth PM in eighteen particularly rough months, and as a relative unknown, seemed an expendable who likewise would be sacked in due time. But he found a lever that allowed him to stay on, and by the estimates of a growing body of opinion, the feared fascist regime came to power in Moscow despite the best efforts of the internationalists.

Next: Terror of 9/99, Putin Ascendant

Sources:

[1] Brzezinski p. 118.

[2] Brz 100-101

[3] Williamson, Anne. “The Rape of Russia.” Testimony before Committee on Banking and financial Services, US House of Representatives. September 21 1999. http://www.russians.org/williamson_testimony.htm

[4] Ruppert - Crossing the Rubicon - easily controlled with money

[5] Ruppert page 88

[6] Brzezinski p 99.

[7] BRZ 109.

[8] Brz 107

[9] “Russian Trains: New Kiriyenko government faces first major test.” CNN. May 20, 1998. http://cnn.hu/WORLD/europe/9805/20/russia.govt.crisis/

[10] Ruppert – kiss of death

[11], [12] IMF protected US banks in Russian bailout. By Nick Beams. 21 July 1998. World Socialist Web Site. http://www.wsws.org/news/1998/july1998/rus-j21.shtml

[13] "The IMF's $22.6 Billion Failure in Russia." Ariel Cohen, Ph.D., and Brett D. Schaefer. Heritage Foundation Executive Memorandum #548. http://www.heritage.org/Research/RussiaandEurasia/em548.cfm

[14] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Abramovich

[15] IMF protected US banks in Russian bailout. By Nick Beams. 21 July 1998. World Socialist Web Site. http://www.wsws.org/news/1998/july1998/rus-j21.shtml

Adam Larson

Caustic Logic / Guerillas Without Guns

Re-posted 2/17/07

For Washington and London, the ability to start making these pipeline power plays was both an effect and hopefully a further cause of Russia’s diminished regional power. Behind this seems to be a campaign to drag the Eurasian giant into the Euro-Atlantic Community kicking and foaming at the mouth if need be, an aim laid out well by Brzezinski in 1997: “Russia’s only real geostrategic option – the option that could give Russia a realistic international role and also maximize the opportunity of transforming and socially modernizing itself - is […] the transatlantic Europe of the enlarging EU and NATO.” Russia should follow this lead, Brzezinski warned, if it wanted to avoid “a dangerous geopolitical isolation.” [1]

But the exact terms of integration remained unclear; Russians somehow took Washington’s talk around 1992-93 of a “mature strategic partnership” as a revival of Gorbachev’s “new world order” scenario, a more-or-less co-equal global alliance of mutually existing great powers. Fawning praise, false promises, and the opening of economies ensued in a long and nearly snuggly phase that allowed what Brzezinski summed up as the Russian street’s expectation of “a global condominium.” Zbig noted in retrospect:

“The problem with this approach was that it was devoid of either international or domestic realism. While the concept of a “mature strategic partnership” was flattering, it was also deceptive. America was neither inclined to share global power with Russia nor could it, even if it had wanted to. […] once differences inevitably started to surface, the disproportion in political power, financial clout, technological innovation and cultural appeal made the “mature strategic partnership” seem hollow – and it struck an increasing number of Russians as deliberately designed to deceive Russia.” [2]

So it was not America’s fault, but the fact that Russia was simply not up to the role. But the 1990s did see economic liberalization in Yeltsin’s Russia, with the widespread privatization of the previously state-run enterprises and moves towards a full market economy, openness to foreign investment, and general integration with the Western system. The major enterprises were taken over by a new generation of Russian capitalist pioneers and black-marketeers known as “the Oligarchs.” First introduced to the scene by Gorbachev in the late 1980s under his perestroika campaign, President Yeltsin supported this process and provided the Oligarchs with rich pickings, and the very small group soon acquired vast interests in all sectors of the economy. But in the end analysis, everyone agrees that the oligarchs did not rescue the Russian economy but rather bled it dry. Journalist Ann Williamson, author of How America Built the New Russian Oligarchy, explained to the House Committee on Banking in her September 1999 testimony:

“Directors stashed profits abroad, withheld employees’ wages, and after cash famine set in, used those wages, confiscated profits and state subsidies to ‘buy’ the workers’ shares from them. The really good stuff – oil companies, metal plants, telecoms – was distributed to essentially seven individuals, ‘the oligarchs,’ on insider auctions whose results were guaranteed beforehand. Once effective control was established, directors - uncertain themselves of the durability of their claim to newly acquired property - chose to asset strip with impunity instead of developing their new holdings.” [3]

Profits thus gained were laundered and deposited safely in Western bank accounts outside of Russia’s reach, with the depositors sometimes following their money out the door. Passed off as the result of mismanagement and shortsighted greed, the draining of Russia’s treasury is usually termed as “capital flight,” a rather passive sounding process. But investigator Michael Ruppert sees geopolitics at work in this “scheme to loot Russia’s wealth and park it in the west.” Once they were granted positions of economic power, Ruppert maintained in his 2004 book Crossing the Rubicon that “the Empire loved the oligarchs because they were simple and could be easily controlled with money.” [4]

Ruppert also noted how the “assistance” program to usher Russia into capitalism took off under the Clinton administration in 1993. A team headed by vice president Al Gore worked in concert with Goldman Sachs, Harvard’s Institute for International Development, the IMF, and the World Bank. This team, as Ruppert summarized, “worked in partnership with the government of Boris Yeltsin to re-make the Russian economy. What happened was that Russia, in the words of Yeltsin himself, became a “mafiocracy” and was looted of more than 500 billion in assets, and its ability to support a world-class military establishment smashed.” [5] What a convenient turn of events against this recently identified potential rival.

Yeltsin had initially renounced all claim to former Soviet glory and empire: “Russia does not aspire to become the center of some sort of new empire […] history has taught us that a people that rules over others cannot be fortunate.” [6] But by 1997 as Brzezinski wrote his book, new ideas about Russia’s role were starting to gel in Moscow that showed signs of renewed ambition. Straddling the boundary between Europe and Asia, the idea of a special “Eurasianism” took hold; as Yeltsin’s former Vice President Aleksandr Rustkoi explained “Russia represents the only bridge between Asia and Europe. Whoever becomes the master of this space will become the master of the world.” [7] Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev said at around this time Russia “must preserve its military presence in regions that have been in its sphere of interests for centuries.” [8]

But not much was possible with the economy still in a weak transitional state. The first slight economic recovery began in 1997, but this was cut short by the Asian financial crisis that hit its markets late in the year. The nation toughed out the financial burden through the first half of 1998, but things got edgy as the money dried up. In May a campaign of pensioner’s strikes was joined by miner’s strikes and others – the people took matters into their own hands, blocking railway lines to demand unpaid back wages. Communist leader Gennady Zyuganov led the growing calls for Yeltsin and his newly-appointed PM Sergei Kiryenko to resign. [9]

Perhaps in desperation, Russia finally turned to the West and sought an IMF bailout, what Ruppert calls “the kiss of death for any country.” [10] The IMF reported it was strapped, and “entering a region in terms of our financing where we are in grave difficulties.” [11] Washington feared the alternative – a Russian devaluation of the ruble (their equivalent of the dollar), leading to an international financial chain reaction. [12] On July 20, the IMF Executive Board approved its portion ($11.2 billion) of a $22.6 billion international bailout. This emergency package was intended to help Russia maintain the value of the ruble while the government implemented reforms necessary to create long-term stability.

|

Mass unemployment and a sharp fall in living standards for most of the population ensued. Unemployment, hunger, homelessness, and related social problems wracked the region in late 1998. CNN billed “Russia’s year of agony” as one of the top ten stories of the year, and it also spread into neighboring countries like Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, that remained tangled with their neighbor’s economy. Many in Washington were furious; Ariel Cohen and Brett Schaefer of the Heritage Foundation noted “it is now painfully clear […] that the massive bailout failed in both of its missions: The ruble was devalued, and reforms are not likely to be implemented.” Cohen and Schaefer blamed Russia for failing to reform its economy and the IMF for consistently loaning to them anyway, calling on Congress to cut off funding to the fund. [13]

The crisis did not last too long though on the Russian end; by whatever connection, it was only after the loan and the devaluation of the ruble and the debt default that Russia’s economy began improving on the back of strong gas exports in 1999. The weak ruble made imports expensive and boosted local production, creating greater self-reliance or “autarky,” the opposite of the economic “dependency model” behind the western system. Russia entered a phase of rapid economic expansion, the GDP growing by an average of 6.7% annually in 1999-2005 on the back of higher oil prices, a weaker ruble, and increasing industrial output. It has gone from bankruptcy to large foreign reserves, and by 2001 Russia was seen as a major rising player on the world scene for the first time in nearly a decade. In retrospect the IMF episode almost looks like a grand kiss-off to the West: “Thanks for the so-called assistance, comrades, but we’ll just recover what we can and manage it ourselves from there...”

Behind the official reasons for the 1998 bailout there had been deeper fears than the value of the ruble. The youngest and richest among the economy draining Russian Oligarchs is Roman Abramovich, in 2006 Russia’s richest man and the 11th richest person in the world, worth $18.2 billion. [14] Abramovich is a proud Jew and supporter of Israel, and he’s not alone; the top tier of Oligarchs were primarily Jews, a fact that contributed negatively to a trend all too familiar from the history books: a nation in crisis after losing a major struggle, feeling betrayed by the West and turning to renewed nationalist glory and – at least in certain cases - increased suspicion of the Jews among them. The specific anti-Semitism has of course become highly unpopular since the Holocaust, and precise charges have remained muted – but overall a repeat of Germany circa 1932 seemed a danger; the British free trade magazine The Economist ran a story on July 15 warning that an abrupt devaluation:

“could spell doom for the banking system, bring down the Kiriyenko government and, as one American diplomat put it, ‘signal the end of liberal Russia.’ […] Might the deadly mixture of economic chaos, public anger and sense of national humiliation that fuelled fascism in Weimar Germany flare up in Russia now? […] Such fears appear to have been taken seriously enough in Washington for the US administration to deem the situation in Russia to be a global strategic threat."[15]

Five days after this story ran the package was approved, but on this front as well the bailout seems to have had little effect. Prime Minister Kiriyenko was sacked in August. Yeltsin tried to bring back his predecessor Viktor Chernomyrdin, but in September compromised on Yevgeniy Primakov. In May 1999 Yeltsin sacked Primakov, replacing him with Sergey Stepashin, who served until August when Yeltsin replaced him with rising star Vladimir Putin. Putin was thus the fifth PM in eighteen particularly rough months, and as a relative unknown, seemed an expendable who likewise would be sacked in due time. But he found a lever that allowed him to stay on, and by the estimates of a growing body of opinion, the feared fascist regime came to power in Moscow despite the best efforts of the internationalists.

Next: Terror of 9/99, Putin Ascendant

Sources:

[1] Brzezinski p. 118.

[2] Brz 100-101

[3] Williamson, Anne. “The Rape of Russia.” Testimony before Committee on Banking and financial Services, US House of Representatives. September 21 1999. http://www.russians.org/williamson_testimony.htm

[4] Ruppert - Crossing the Rubicon - easily controlled with money

[5] Ruppert page 88

[6] Brzezinski p 99.

[7] BRZ 109.

[8] Brz 107

[9] “Russian Trains: New Kiriyenko government faces first major test.” CNN. May 20, 1998. http://cnn.hu/WORLD/europe/9805/20/russia.govt.crisis/

[10] Ruppert – kiss of death

[11], [12] IMF protected US banks in Russian bailout. By Nick Beams. 21 July 1998. World Socialist Web Site. http://www.wsws.org/news/1998/july1998/rus-j21.shtml

[13] "The IMF's $22.6 Billion Failure in Russia." Ariel Cohen, Ph.D., and Brett D. Schaefer. Heritage Foundation Executive Memorandum #548. http://www.heritage.org/Research/RussiaandEurasia/em548.cfm

[14] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Abramovich

[15] IMF protected US banks in Russian bailout. By Nick Beams. 21 July 1998. World Socialist Web Site. http://www.wsws.org/news/1998/july1998/rus-j21.shtml

Saturday, February 17, 2007

UKRAINE’S FATE AND THE BRZEZINSKIS FLANKING IT

|

A FAMILY PROJECT

Adam Larson

Caustic Logic / Guerillas Without guns

posted 2/17/07

last edited: 2/27/07

In the context of a great game with Russia, the emphasis on Ukraine is understandable - it had been the 2nd most powerful Republic in the USSR and its agricultural heartland. It is the birthplace of the Kievan Rus, the original Slavic culture that Russians trace their own culture back to. It is home to about 10 million ethnic Russians, roughly 20 percent of the entire population there, shares hundreds of miles of common border with Russia, and provides a historically useful buffer space from European invasions, which seem to occur every so often. It has absorbed Napoleonic and Nazi assaults, massive famine, and the Chernobyl disaster and continues to be one of Russia’s biggest trading partners and the place most Russian gas pipelines to Europe run through. Clearly, Ukraine as a geopolitical prize is epic; it’s the biggest thing one can take from Russia besides Russia itself. It seems a stretch to even attempt such a move, but apparently the successes of Belgrade and Tbilisi had left some people feeling very cocky.

American designs on securing Ukraine in the Western camp go back at least to 1997, when Zbigniew Brzezinski, in his book The Grand Chessboard, described Ukraine as one of five key “geopolitical pivots” for control of Eurasia (the others being Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, and South Korea). Furthermore, the CFR heavyweight pointed to Ukraine as the final target in extending the “democratic bridgehead” - the contiguous chain of pro-West Democracies like France and Poland - across Europe and right to Russia’s doorstep. An article in Foreign Relations (the official publication of the CFR) explained that this was targeted against Russia: “[T]he heart of the book is the ambitious strategy it prescribes for extending the Euro-Atlantic community eastward to Ukraine and lending vigorous support to the newly independent republics of Central Asia and the Caucasus, part and parcel of what might be termed a strategy of “tough love” for the Russians” Even the magazine noted a bit too much tough in the love: “Brzezinski's test of what constitutes legitimate Russian interests is so stringent that even a democratic Russia is likely to fail it.”

And this tough love ran in the family, with Brzezinski’s son Ian having been an advisor to the newly-independent Ukrainian parliament (director of international security policy at the Council of Advisers) from 1993-94, while also serving as Executive Director of the CSIS American-Ukrainian Advisory Committee. Note that Brzezinski’s tenure ended in the same year Kuchma came to power and turned the country east. Ian has since then continued lobbying from the outside to bring Ukraine into the EU-NATO fold. “Ukraine should be a central component of the West's strategy for Europe.” the younger Brzezinski explained to congress in 1999. But before the adoption could be completed:

“Ukraine will have to make, on its own, the difficult internal decisions necessary to overcome its economic stagnation, its rampant corruption, and its polarized politics. […] After a decade of billions of dollars of Western assistance, the initiative must now come foremost from a Ukraine characterized by aggressive reform.”

Ian was appointed shortly after 9/11 to be the Pentagon’s representative to its European NATO partners and a pivotal part of the decision of who will join next. But his hopes of internal reform started to seem less likely as 2004 dawned with President Kuchma and the PM set to take his place disinterested in such changes and steadily gravitating to the East and Moscow’s sphere.

This is where Viktor Yushchenko, Pora!, dioxin, and the Orange Revolution come in.

After coming to power in Kiev, Yuschchenko played well to Western audiences from day one. When he made his first visit to Washington in early April 2005, he gave a rousing speech to the assembled Congress, receiving a standing ovation as the hero of the Orange Revolution, a white Nelson Mandela who had suffered poisoning, not prison. It is relatively rare, and usually considered a high honor, for a foreign leader to be invited to address a joint session of Congress. CNN ran live coverage, and was sure to have Mark Brzezinski - Ian’s brother – present for analysis. The onetime director for Russian and Eurasian Affairs for the National Security Council and foreign policy advisor to the John Kerry presidential campaign was hopeful that Yushchenko could “show the Ukrainian people that he can not only talk the talk, but walk the walk in terms of essential transformations within Ukraine.”

On a working visit to Poland at the end of August, a still faintly scarred Yushchenko had a photo taken with Ian and Mark’s father, the exalted Zbigniew Brzezinski in the land of his birth. They clasped hands and gazed smilingly at each other as NDI’s Madeleine Albright looked on with a grin. The “democratic bridgehead” had been extended as Zbig had prescribed eight years earlier, and he seemed very happy about the whole affair. The decade-running family project had yielded tangible gains, but the situtaion would soon complicate and the smiles would fade.

|

Labels:

Brzezinski I,

Brzezinski M,

Brzezinski Z,

Europe,

Grand Chessboard,

Kuchma,

NATO,

Poland,

Russia,

Ukraine

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)